Japanese Haiku and Matsuo Basho

Furuike ya

Kawazu tobikomo

Mizo no oto.

Old pond

Frog jumps in

Water-sound.

Classical Japanese literature most famous gift to the West, and to American literature in particular, has been an unlikely one for our democracy to embrace, the poetic form, austere even by Japanese standards, called "haiku." A haiku (the word is both singular and plural) is a poem only 17 syllables long, written in three lines of five, seven, and five syllables.

The name is pronounced ha i ku, in three syllables, because in Japanese there are no diphthongs; but English speakers normally say it in two syllables, "haiku." Any other pronunciation would be, by now, pedantic.

Donald Keene, in his definitive account of Japanese poetry, resolutely uses the word haikai. Keene argues, no doubt rightly, that the "word and the concept" of haiku, the idea that the three lines stood by themselves as a separate poem, dated only from the late 1800s. Be that as it may, Western culture has already embraced the word "haiku," and we will not use the right word anymore than we will correctly call Rome, "Roma."

During the 1960s, Harold G. Henderson excellent translations of haiku became a kind of beatnik/hippie bible, resting on the living room table next to the copy of Hesse Siddhartha and the water pipe. Since the turn of the century, moreover, poetry called haiku had inspired Western poets, first in France, and then among the important poets affiliated with Ezra Pound. Pound famous attempt at a haiku equivalent is one of his best poems. He captures a scene on London Underground (subway):

Faces In the crowd

Petals on a wet, black bough.

The example of haiku (among other forms) licensed Pound, Amy Lowell, and certain other "Imagist" poets to write the kind of poetry they longed to write anyway. They knew little of Japan; few Westerners did, at the time; and much of what they "knew" was "orientalist" fantasy. Perhaps they didn't even care. They were using haiku example to excuse themselves from the tyranny of English rhyme and to destroy the traditional English esteem for poetry that was (like so much English poetry, from Ben Jonson to Tennyson) a versification of arguments, short stories and monologs told in verse instead of prose.

In its place they elevated the idea (perhaps the mistaken idea) of an Asian lyric poetry that communicated by images alone. "No ideas but in things." Haiku frequent obscurity and suggestiveness also helped Pound and company create the twentieth-century poetic convention that a poem need not be understandable on the first reading -- or even the fifty-first. Poets as distant from Pound as Wallace Stevens have taken advantage of that once-controversial permission.

Asian American artists have been justifiably proud of haiku prestige in the West. For instance, Hisaye Yamamoto short story collection, Seventeen Syllables, which Jeffery Chan considers the finest by a Japanese American so far, takes its name from haiku, the art of creating a poem in 17 syllables.

The Evolution of the Haiku Form

Why base a poetic form on syllable count, rather than on rhyme, as so much of Western poetry does? All Japanese words end either in a vowel or an "n" which makes rhyming too easy. It almost as easy, in Japaneses, to rhyme as not to rhyme.

The history of Japanese poetry -- at least the history that leads to the invention of the haiku -- shows a growing fascination with the beauty of concision, of understatement, and with the power of suggestion. As far back as the Heian era (794-1191) a 31-syllable form (called "tanka" and also "waka") was being written among the idling nobles at court, often answered by a similar poem. These linked verses -- up to 100 verses long -- were called "renga." We are told that they were sometimes written by courtier poets sitting together almost like jazz artists, listening to each other poems and, on the spot, answering riffs, altering and extending the themes. (A great theme for an online chat room?) The themes were typical of court poets in all cultures: ennui and dalliance, the brevity of love, youth, life, conveyed in ritualized melancholic allusions to fading blossoms, vanished summers, and such.

This friendly but competitive atmosphere led to a gradual lightening of the rules-of-play and a growing sense of seriousness. Teitoku (1571-1653), though his work stayed on the level, Keene tells us, of "witticisms," was the dominating poet of his age, and his seriousness about his haikai lent the genre his prestige. Soin (1605-1682) and Saikaku (1642-1693) are credited with keeping the 31-syllable tanka form colloquial language and wit, but investing the genre with a new seriousness. They developed certain tactics that classic haiku would later employ: a fondness for images rather than for explanations, and for jumpcuts between those images that cause interesting and suggestive clashes. The poems work, at their best, the way film works, by a rapid montage of images that generate a meaning of their own.

By Soin time, the 1600s, the 31-syllable tanka had, for several hundred years, begun with a three-line starting verse, using the first 17 syllables. The Japanese for "starting verse" is hokku. Gradually, that starting verse became the whole poem, called "haiku" (and as we have noted, in scrupulous texts, haikai).

Interest in upping the ante and showing you could do in 17 syllables what some other courtly poet needed 31 to do, dates back at least to the mid 1200s. These early haiku examples are very primitive -- almost like greeting card verses. The poets are still essentially courtly wits. You can usually paraphrase what these early haiku mean in ordinary prose -- a bad sign.

Soin new artistic school ended that. In 1660, the same year as the English Restoration, Soin founded the "Damrin school," and haiku rose toward high art while it simultaneously became intimately connected with the Zen Buddhist vision. (For a full discussion of Zen, see Chapter 37.) No one disputes Soin historical importance. However, all authorities agree that Soin student, Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) is the genius who perfects haiku.

Matsuo Basho

To understand Basho relationship to all subsequent haiku, one has to think of Shakespeare relationship to all subsequent English poetry. I could stretch the parallel and claim Soin as Basho Christopher Marlowe, a great innovator who sows many of the seeds Shakespeare will harvest. Marlowe began writing verse dramas in English iambic pentameter "Marlowe mighty line" lifting the form to high art. Shakespeare, his younger contemporary, perfects English iambic pentameter and the drama based on it.

Indeed, as the critic Harold Bloom has pointed out, Shakespeare, in a way, succeeds too well. Who, after all, would want to write a verse drama now? Shakespeare so fully exploited the form possibilities that his followers have been reduced to imitation, veneration, or flight. Similarly, Basho not only perfected haiku, he put such a strong stamp on it that to this day haiku poets cannot escape him. The difference is that English verse drama was virtually given up within a century of Shakespeare death, but haiku continues to thrive in Japan.

The poem quoted at the beginning of this article is Basho masterpiece and still his most famous. (Japanese grammar is so different from English that my translation is merely one of a hundred possible.) It was published in 1686, when Basho was already 42 years old, well known, and surrounded by disciples.

The child of minor samurai (the knightly or warrior class), he had rebelled against his parents, traveled restlessly around Japan enduring spiritual trials -- sometimes sampling the fleshly pleasures of the geisha "floating world" -- and writing poetry. In 1675 he was well enough known for the great Soin to invite him, among others, to compose renga, the linked form. Basho was deeply honored and adopted a new pen name to signal his transformation. He becomes, for a time, almost too respectful a disciple, writing Soin-like verses.

But his personal spiritual crises returned: in his poems black crows descend on him, his "guts freeze," he weeps through the black night. His spiritual trials, so familiar to Western poets and their readers since the Romantics, made his poetry feel accessible to American poetry readers later.

At last, Basho sought solace in Zen meditation. After the "Zen boom" of the beatnik nineteen-fifties, that solution was familiar to American poetry audiences too. After several years of sitting in meditation, trying to erase his personality, to simply be and see the scene in front of him, Basho escaped the torments of his middle years and entered a calm visionary place he never left.

Haiku becomes, in his hands, a door through which others reach his contemplative visions, achieve his sensation of ultimate reality in even the most commonplace things.

Harold Henderson, in an incisive passage, summed up how Zen perfected Basho character and his poetry. After Zen his poems showed a "great zest for life; a desire to use every instant to the uttermost; an appreciation of this even in natural objects; a feeling that nothing is alone, nothing unimportant; a wide sympathy; and an acute awareness of relationships of all kinds, including that of one sense to another."

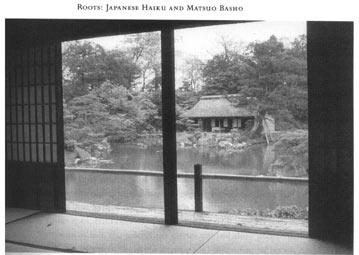

Figure 35-l: Teahouse and lake, Katsura imperial Villa, Kyota, Japan. Early 1600s. Basho and his disciples were reclining in such a pavilion when a frog leaped into the lake, leading Basho to compose his most famous haiku. Photo by George Leonard.

Comparisons with Wordsworth and other "natural Supernaturalists" are frequent, and valid, but considering Basho poems' sheer intensity, comparisons with Van Gogh would be better. Van Gogh does not paint scenes; he paints his experiences of scenes. Millet paints a Starry Night and we know how it looked. Van Gogh paints a Starry Night, and we know how it felt to be Van Gogh, standing there in holy awe. The painting is still of stars, not of angels; but the stars seem to pinwheel with the joy of sheer being, while beneath them, cypresses twist and burn in the ecstasy of being alive. In Van Gogh paintings, ordinary trees and fields take on a holiness and awesomeness, without his having to add supernatural elements. In Basho work, too.

Such moments have been called, since James Joyce, "epiphanies," moments when the holiness shines through commonplace things. The more commonplace, the better -- we need help with those the most. There is no way to write a prose paraphrase of the Basho poem quoted above. How to explain the mystical quality that centuries of readers have agreed Basho successfully gives that moment? Even in translation, much comes across:

Old pond

Frog jumps in

Water-sound.

A disciple has left us a memory of the instant the poem was written. Basho was deep in meditation, sitting in a covered area outside his riverside house, listening to the silence, to some pigeons cooing faintly, to a gentle misting rain. Now and then came the sound of a frog leaping into the water. Basho suddenly recited the last two lines. But he had no opening line. A disciple then suggested a showy opening line, something about all this happening in the midst of yellow roses. Basho quietly refused, and added "Old pond." Some translations try to explain the poem ("Breaking an old pond holy silence," and so forth) but Basho simplicity needs no help.

One critic uncovered some of Basho concealed craft by remarking that much of the effect would vanish if Basho had just written:

Pond

Frog jumps in

Water-sound.

Basho slight but significant addition to the visual and auditory facts -- "old pond" -- wafts just enough feeling of age and peace over the scene to make it work. Yet, I must insist that, as with Van Gogh paintings, if we really knew how he did it, we could do it too. We don't and we can't.

Basho ability to create this effect in only 17 syllables gives his haiku a power that Western aesthetics has long recognized. That which strikes in an instant has more force than that which takes two hours to produce its effects. Thus Western historical painting argued its superiority, since Horace time, to works written down on paper. Basho's poems work on us as rapidly as a painting, and they strike as hard. They are not little, they're brief, and that is power. Hemingway (writing in praise of his own understated art) said that "the dignity of an iceberg lies in its being nine-tenths beneath the water." You sense, in Basho poems, that you have glimpsed only the tip of a stately vastness beneath.

Basho was master of another form as well. In "travel diaries" like Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North), he wrote introspective prose which rises, when it needs to, like an opera rising from recitative to an emotional aria, into lyrical haiku. These are no mere travel diaries, of course. As Henderson points out, the ambiguous title could almost be translated, "the difficult path to the interior" --of the self? of Japan? of being? Basho art is an art of infinite suggestion.

Haiku After Basho

After Basho, the form does not lack for great names, but this is a book to be used as background by the West, not a study of Japanese poetry in itself; and for the West, Basho has, historically, been haiku itself. The interested reader certainly should go on to read:

--Onitsura (1660-1738) who studied with Soin school. He is sometimes as visionary as Basho. Onitsura once said, "Outside of truth there is no poetry."

--The melancholy, gentle Issa (l762-1826) reminds one of the French painter Watteau, and like him, works on the edge of sentiment. At times he goes over the edge into sentimentality.

--Buson (1715-1783) is a great craftsman, but he is as different from Basho as the worldly Parisians Manet and Degas are from the devout Van Gogh. Busons sophisticated poems about prostitutes, for instance, are the work of a boulevardier, as are Manet wry paintings of cafe life.

--Shiki (1867-1902) who lived during the frantic attempt to Westernize Japan, writes as religiously as Basho does, but militantly rejects Buddha ("I'll have no gods or Buddhas!"). He wants to kick the priests and clerics out and show people they can see the world as a miracle without buying into a lot of theological bureaucracy. Like the similarly militant atheist Percy Shelley, he even writes a poem about a skylark. Like Monet, he embraces the new industrial world, and tries to include not only nature in his poems, but the beauty of railroads and modern industrial objects.

For all that, none ever equals Matsuo Basho. As with Shakespeare case, no one is expected to.

Further Reading

Basho, Matsuo. The Narrow Road to the Deep North, and Other Travel Sketches. Trans. by Nobuyuki, Yuasa. New York: Penguin, 1966.

Henderson, Harold G. An Introduction to Haiku. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1918. Popular, unsurpassed lyrical translations, by Donald Keene predecessor at Columbia. The best and most familiar English versions of the most famous haiku.

Keene, Donald. World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1601-1867. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976.Tbe definitive work (600 pages) by Columbia University master scholar and translator. Nearly 300 pages on haiku and its related forms alone.